Deadlocks

System Model

For the purposes of deadlock discussion, a system can be modeled as a collection of limited resources, which can be partitioned into different categories, to be allocated to a number of processes, each having different needs.

By definition, all the resources within a category are equivalent, and a request of this category can be equally satisfied by any one of the resources in that category. If this is not the case ( i.e. if there is some difference between the resources within a category ), then that category needs to be further divided into separate categories. For example, "printers" may need to be separated into "laser printers" and "color inkjet printers".

In normal operation a process must request a resource before using it, and release it when it is done, in the following sequence:

- Request - If the request cannot be immediately granted, then the process must wait until the resource(s) it needs become available. For example the system calls open( ), malloc( ), new( ), and request( ).

- Use - The process uses the resource, e.g. prints to the printer or reads from the file.

- Release - The process relinquishes the resource. so that it becomes available for other processes. For example, close( ), free( ), delete( ), and release( ).

A set of processes is deadlocked when every process in the set is waiting for a resource that is currently allocated to another process in the set ( and which can only be released when that other waiting process makes progress. )

Deadlock Characterization

There are four conditions that are necessary to achieve deadlock:

- Mutual Exclusion - At least one resource must be held in a non-sharable mode; If any other process requests this resource, then that process must wait for the resource to be released.

- Hold and Wait - A process must be simultaneously holding at least one resource and waiting for at least one resource that is currently being held by some other process.

- No preemption - Once a process is holding a resource ( i.e. once its request has been granted ), then that resource cannot be taken away from that process until the process voluntarily releases it.

- Circular Wait - A set of processes { P0, P1, P2, . . ., PN } must exist such that every P[ i ] is waiting for P[ ( i + 1 ) % ( N + 1 ) ]. ( Note that this condition implies the hold-and-wait condition, but it is easier to deal with the conditions if the four are considered separately. )

Resource-Allocation Graph

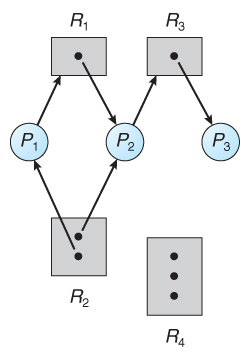

In some cases deadlocks can be understood more clearly through the use of Resource-Allocation Graphs, having the following properties:

- A set of resource categories, { R1, R2, R3, . . ., RN }, which appear as square nodes on the graph. Dots inside the resource nodes indicate specific instances of the resource. ( E.g. two dots might represent two laser printers. )

- A set of processes, { P1, P2, P3, . . ., PN }

- Request Edges, A set of directed arcs from Pi to Rj, indicating that process Pi has requested Rj, and is currently waiting for that resource to become available.

- Assignment Edges, A set of directed arcs from Rj to Pi indicating that resource Rj has been allocated to process Pi, and that Pi is currently holding resource Rj.

- Note that a request edge can be converted into an assignment edge by reversing the direction of the arc when the request is granted. ( However note also that request edges point to the category box, whereas assignment edges emanate from a particular instance dot within the box. )

- If a resource-allocation graph contains no cycles, then the system is not deadlocked. ( When looking for cycles, remember that these are directed graphs. )

- If a resource-allocation graph does contain cycles AND each resource category contains only a single instance, then a deadlock exists.

- If a resource category contains more than one instance, then the presence of a cycle in the resource-allocation graph indicates the possibility of a deadlock, but does not guarantee one.

Handling Deadlocks

Generally speaking there are three ways of handling deadlocks:

- Deadlock prevention or avoidance - Do not allow the system to get into a deadlocked state.

- Deadlock detection and recovery - Abort a process or preempt some resources when deadlocks are detected.

- Ignore the problem all together - If deadlocks only occur once a year or so, it may be better to simply let them happen and reboot as necessary than to incur the constant overhead and system performance penalties associated with deadlock prevention or detection. This is the approach that both Windows and UNIX take.

In order to avoid deadlocks, the system must have additional information about all processes. In particular, the system must know what resources a process will or may request in the future. ( Ranging from a simple worst-case maximum to a complete resource request and release plan for each process, depending on the particular algorithm. )

Deadlock detection is fairly straightforward, but deadlock recovery requires either aborting processes or preempting resources, neither of which is an attractive alternative.

If deadlocks are neither prevented nor detected, then when a deadlock occurs the system will gradually slow down, as more and more processes become stuck waiting for resources currently held by the deadlock and by other waiting processes. Unfortunately this slowdown can be indistinguishable from a general system slowdown when a real-time process has heavy computing needs.

Deadlock prevention

Deadlocks can be prevented by preventing at least one of the four required conditions:

Mutual Exclusion

- Shared resources such as read-only files do not lead to deadlocks.

- Unfortunately some resources, such as printers and tape drives, require exclusive access by a single process.

Hold and Wait

To prevent this condition processes must be prevented from holding one or more resources while simultaneously waiting for one or more others. There are several possibilities for this:

- Require that all processes request all resources at one time. This can be wasteful of system resources if a process needs one resource early in its execution and doesn't need some other resource until much later.

- Require that processes holding resources must release them before requesting new resources, and then re-acquire the released resources along with the new ones in a single new request. This can be a problem if a process has partially completed an operation using a resource and then fails to get it re-allocated after releasing it.

- Either of the methods described above can lead to starvation if a process requires one or more popular resources.

No Preemption

Preemption of process resource allocations can prevent this condition of deadlocks, when it is possible.

- One approach is that if a process is forced to wait when requesting a new resource, then all other resources previously held by this process are implicitly released, ( preempted ), forcing this process to re-acquire the old resources along with the new resources in a single request, similar to the previous discussion.

- Another approach is that when a resource is requested and not available, then the system looks to see what other processes currently have those resources and are themselves blocked waiting for some other resource. If such a process is found, then some of their resources may get preempted and added to the list of resources for which the process is waiting.

- Either of these approaches may be applicable for resources whose states are easily saved and restored, such as registers and memory, but are generally not applicable to other devices such as printers and tape drives.

Circular Wait

- One way to avoid circular wait is to number all resources, and to require that processes request resources only in strictly increasing ( or decreasing ) order.

- In other words, in order to request resource Rj, a process must first release all Ri such that i >= j.

- One big challenge in this scheme is determining the relative ordering of the different resources

Deadlock Avoidance

The general idea behind deadlock avoidance is to prevent deadlocks from ever happening, by preventing at least one of the aforementioned conditions.

This requires more information about each process, AND tends to lead to low device utilization. ( I.e. it is a conservative approach. )

In some algorithms the scheduler only needs to know the maximum number of each resource that a process might potentially use. In more complex algorithms the scheduler can also take advantage of the schedule of exactly what resources may be needed in what order. When a scheduler sees that starting a process or granting resource requests may lead to future deadlocks, then that process is just not started or the request is not granted.

A resource allocation state is defined by the number of available and allocated resources, and the maximum requirements of all processes in the system.

Safe State

A state is safe if the system can allocate all resources requested by all processes ( up to their stated maximums ) without entering a deadlock state.

More formally, a state is safe if there exists a safe sequence of processes { P0, P1, P2, ..., PN } such that all of the resource requests for Pi can be granted using the resources currently allocated to Pi and all processes Pj where j < i. ( I.e. if all the processes prior to Pi finish and free up their resources, then Pi will be able to finish also, using the resources that they have freed up. )

If a safe sequence does not exist, then the system is in an unsafe state, which MAY lead to deadlock. ( All safe states are deadlock free, but not all unsafe states lead to deadlocks. )

Resource-Allocation Graph algorithm

If resource categories have only single instances of their resources, then deadlock states can be detected by cycles in the resource-allocation graphs.

In this case, unsafe states can be recognized and avoided by augmenting the resource-allocation graph with claim edges, noted by dashed lines, which point from a process to a resource that it may request in the future.

In order for this technique to work, all claim edges must be added to the graph for any particular process before that process is allowed to request any resources. ( Alternatively, processes may only make requests for resources for which they have already established claim edges, and claim edges cannot be added to any process that is currently holding resources. )

When a process makes a request, the claim edge Pi->Rj is converted to a request edge. Similarly when a resource is released, the assignment reverts back to a claim edge.

This approach works by denying requests that would produce cycles in the resource-allocation graph, taking claim edges into effect.

Banker's algorithm

For resource categories that contain more than one instance the resource-allocation graph method does not work, and more complex ( and less efficient ) methods must be chosen.

The Banker's Algorithm gets its name because it is a method that bankers could use to assure that when they lend out resources they will still be able to satisfy all their clients. ( A banker won't loan out a little money to start building a house unless they are assured that they will later be able to loan out the rest of the money to finish the house. )

When a process starts up, it must state in advance the maximum allocation of resources it may request, up to the amount available on the system.

When a request is made, the scheduler determines whether granting the request would leave the system in a safe state. If not, then the process must wait until the request can be granted safely.

The banker's algorithm relies on several key data structures: ( where n is the number of processes and m is the number of resource categories. )

- Available[ m ] indicates how many resources are currently available of each type.

- Max[ n ][ m ] indicates the maximum demand of each process of each resource.

- Allocation[ n ][ m ] indicates the number of each resource category allocated to each process.

- Need[ n ][ m ] indicates the remaining resources needed of each type for each process. ( Note that Need[ i ][ j ] = Max[ i ][ j ] - Allocation[ i ][ j ] for all i, j. )

Safety Algorithm

In order to apply the Banker's algorithm, we first need an algorithm for determining whether or not a particular state is safe.

This algorithm determines if the current state of a system is safe, according to the following steps:

- Let Work and Finish be vectors of length m and n respectively.

- Work is a working copy of the available resources, which will be modified during the analysis.

- Finish is a vector of booleans indicating whether a particular process can finish. ( or has finished so far in the analysis. )

- Initialize Work to Available, and Finish to false for all elements.

- Find an i such that both (A) Finish[ i ] == false, and (B) Need[ i ] < Work. This process has not finished, but could with the given available working set. If no such i exists, go to step 4.

- Set Work = Work + Allocation[ i ], and set Finish[ i ] to true. This corresponds to process i finishing up and releasing its resources back into the work pool. Then loop back to step 2.

- If finish[ i ] == true for all i, then the state is a safe state, because a safe sequence has been found.

A modification to the algorithm:

- In step 1. instead of making Finish an array of booleans initialized to false, make it an array of ints initialized to 0. Also initialize an int s = 0 as a step counter.

- In step 2, look for Finish[ i ] == 0.

- In step 3, set Finish[ i ] to ++s. S is counting the number of finished processes.

- For step 4, the test can be either Finish[ i ] > 0 for all i, or s >= n. The benefit of this method is that if a safe state exists, then Finish[ ] indicates one safe sequence ( of possibly many. ) )

Resource-Request Algorithm ( The Bankers Algorithm )

Now that we have a tool for determining if a particular state is safe or not, we are now ready to look at the Banker's algorithm itself.

This algorithm determines if a new request is safe, and grants it only if it is safe to do so.

When a request is made ( that does not exceed currently available resources ), pretend it has been granted, and then see if the resulting state is a safe one. If so, grant the request, and if not, deny the request, as follows:

- Let Request[ n ][ m ] indicate the number of resources of each type currently requested by processes. If Request[ i ] > Need[ i ] for any process i, raise an error condition.

- If Request[ i ] > Available for any process i, then that process must wait for resources to become available. Otherwise the process can continue to step 3.

- Check to see if the request can be granted safely, by pretending it has been granted and then seeing if the resulting state is safe. If so, grant the request, and if not, then the process must wait until its request can be granted safely.The procedure for granting a request ( or pretending to for testing purposes ) is:

- Available = Available - Request

- Allocation = Allocation + Request

- Need = Need - Request

Deadlock Detection

If deadlocks are not avoided, then another approach is to detect when they have occurred and recover somehow. In addition to the performance hit of constantly checking for deadlocks, a policy / algorithm must be in place for recovering from deadlocks, and there is potential for lost work when processes must be aborted or have their resources preempted.

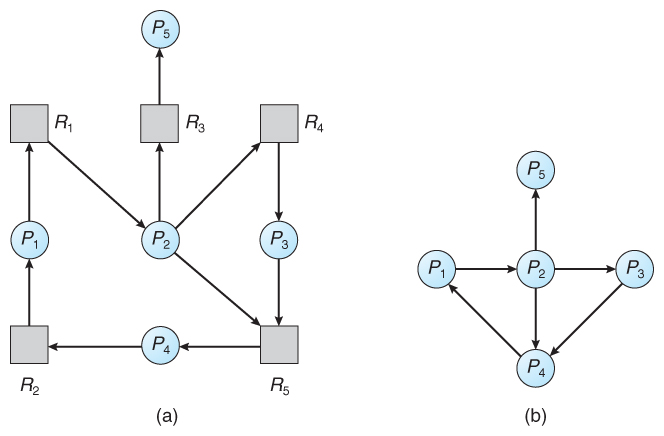

Single Instance of Each Resource Type

If each resource category has a single instance, then we can use a variation of the resource-allocation graph known as a wait-for graph.

A wait-for graph can be constructed from a resource-allocation graph by eliminating the resources and collapsing the associated edges, as shown in the figure below.

An arc from Pi to Pj in a wait-for graph indicates that process Pi is waiting for a resource that process Pj is currently holding.

Several Instance of Each Resource Type

The detection algorithm outlined here is essentially the same as the Banker's algorithm, with two subtle differences:]

- In step 1, the Banker's Algorithm sets Finish[ i ] to false for all i. The algorithm presented here sets Finish[ i ] to false only if Allocation[ i ] is not zero. If the currently allocated resources for this process are zero, the algorithm sets Finish[ i ] to true. This is essentially assuming that IF all of the other processes can finish, then this process can finish also. Furthermore, this algorithm is specifically looking for which processes are involved in a deadlock situation, and a process that does not have any resources allocated cannot be involved in a deadlock, and so can be removed from any further consideration.

- Steps 2 and 3 are unchanged

- In step 4, the basic Banker's Algorithm says that if Finish[ i ] == true for all i, that there is no deadlock. This algorithm is more specific, by stating that if Finish[ i ] == false for any process Pi, then that process is specifically involved in the deadlock which has been detected.

Detection-Algorithm Usage

When should the deadlock detection be done? Frequently, or infrequently?

The answer may depend on how frequently deadlocks are expected to occur, as well as the possible consequences of not catching them immediately. ( If deadlocks are not removed immediately when they occur, then more and more processes can "back up" behind the deadlock, making the eventual task of unblocking the system more difficult and possibly damaging to more processes. )

There are two obvious approaches, each with trade-offs:

- Do deadlock detection after every resource allocation which cannot be immediately granted. This has the advantage of detecting the deadlock right away, while the minimum number of processes are involved in the deadlock. ( One might consider that the process whose request triggered the deadlock condition is the "cause" of the deadlock, but realistically all of the processes in the cycle are equally responsible for the resulting deadlock. ) The down side of this approach is the extensive overhead and performance hit caused by checking for deadlocks so frequently.

- Do deadlock detection only when there is some clue that a deadlock may have occurred, such as when CPU utilization reduces to 40% or some other magic number. The advantage is that deadlock detection is done much less frequently, but the down side is that it becomes impossible to detect the processes involved in the original deadlock, and so deadlock recovery can be more complicated and damaging to more processes.

Recovery from Deadlock

There are three basic approaches to recovery from deadlock:

- Inform the system operator, and allow him/her to take manual intervention.

- Terminate one or more processes involved in the deadlock

- Preempt resources.

Process Termination

Two basic approaches, both of which recover resources allocated to terminated processes:

- Terminate all processes involved in the deadlock. This definitely solves the deadlock, but at the expense of terminating more processes than would be absolutely necessary.

- Terminate processes one by one until the deadlock is broken. This is more conservative, but requires doing deadlock detection after each step.

In the latter case there are many factors that can go into deciding which processes to terminate next:

- Process priorities.

- How long the process has been running, and how close it is to finishing.

- How many and what type of resources is the process holding. ( Are they easy to preempt and restore? )

- How many more resources does the process need to complete.

- How many processes will need to be terminated

- Whether the process is interactive or batch.

- Whether or not the process has made non-restorable changes to any resource.

Resource Preemption

When preempting resources to relieve deadlock, there are three important issues to be addressed:

- Selecting a victim - Deciding which resources to preempt from which processes involves many of the same decision criteria outlined above.

- Rollback - Ideally one would like to roll back a preempted process to a safe state prior to the point at which that resource was originally allocated to the process. Unfortunately it can be difficult or impossible to determine what such a safe state is, and so the only safe rollback is to roll back all the way back to the beginning. ( I.e. abort the process and make it start over. )

- Starvation - How do you guarantee that a process won't starve because its resources are constantly being preempted? One option would be to use a priority system, and increase the priority of a process every time its resources get preempted. Eventually it should get a high enough priority that it won't get preempted any more.