CPU Scheduling

Basic Concepts

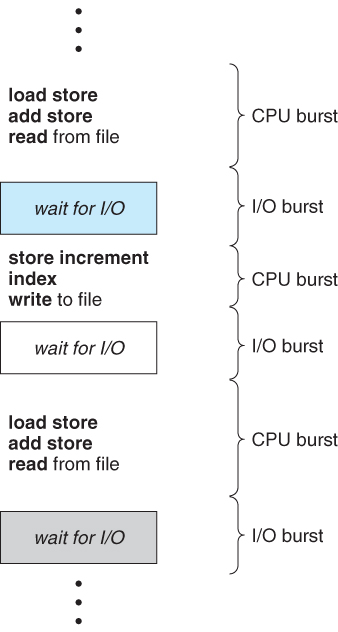

Almost all programs have some alternating cycle of CPU number crunching and waiting for I/O of some kind. ( Even a simple fetch from memory takes a long time relative to CPU speeds. )

In a simple system running a single process, the time spent waiting for I/O is wasted, and those CPU cycles are lost forever. A scheduling system allows one process to use the CPU while another is waiting for I/O, thereby making full use of otherwise lost CPU cycles.

The challenge is to make the overall system as "efficient" and "fair" as possible, subject to varying and often dynamic conditions, and where "efficient" and "fair" are somewhat subjective terms, often subject to shifting priority policies.

CPU Burst cycles

Almost all processes alternate between two states in a continuing cycle

- A CPU burst of performing calculations

- An I/O burst, waiting for data transfer in or out of the system

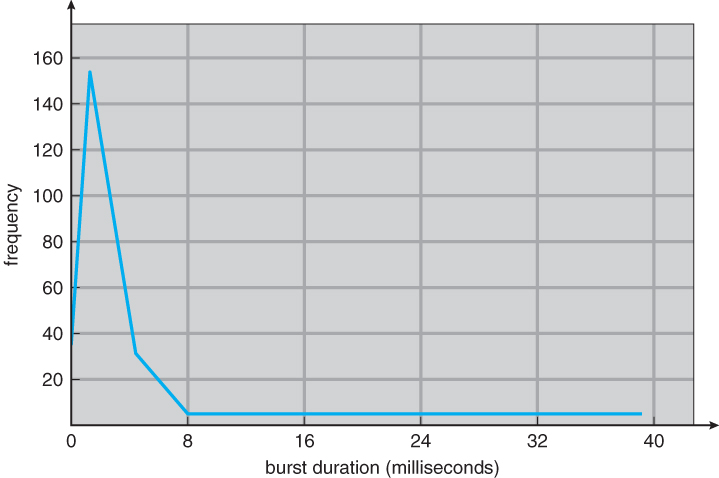

CPU bursts vary from process to process, and from program to program, but an extensive study shows frequency patterns like so:

CPU Scheduler

Whenever the CPU becomes idle, it is the job of the CPU Scheduler ( a.k.a. the short-term scheduler ) to select another process from the ready queue to run next.

The storage structure for the ready queue and the algorithm used to select the next process are not necessarily a FIFO queue. There are several alternatives to choose from, as well as numerous adjustable parameters for each algorithm, which is the basic subject of this entire chapter.

Preemptive Scheduling

CPU scheduling decisions take place under one of four conditions:

- When a process switches from the running state to the waiting state, such as for an I/O request or invocation of the wait() system call.

- When a process switches form teh running state to the ready state, for example in response to an interrupt

- When a process switches from the waiting state to the ready state, for example in response to an interrupt. When a process switches from the waiting state to the ready state, say at completion of I/O or a return from wait().

- When a process terminates.

For conditions 1 and 4 there is no choice, a new process must be selected. For conditions 2 and 3 the choice of either continuing to run the current process or select a different one can be made.

If scheduling takes place only under conditions 1 and 4, the system is said to be non-preemptive, or cooperative. Under these conditions, once a process starts running it keeps running, until it either voluntarily blocks or until it finishes. Otherwise the system is said to be preemptive.

Dispatcher

The dispatcher is the module that gives control of the CPU to the process selected by the scheduler. This function involves:

- Switching context

- switching to user mode

- jumping to the proper location in the newly loaded program

The dispatched needs to be as fast as possible, as it is run on every context switch. The time consumed by the dispatched is known as dispatch latency

Scheduling Criteria

- CPU utilization - Ideally the CPU would be busy 100% of the time, so as to waste 0 CPU cycles. On a real system CPU usage should range from 40% (lightly loaded) to 90% (heavily loaded).

- Throughput - Number of processes completed per unit time, may range from 10 / second to 1 / hour depending on the specific processes.

- Turnaround time - Time required for a particular process to complete, from submission time to completion. (Wall check time)

- Waiting time - How much time processes spend in the ready queue waiting their turn to get on the CPU.

- Load average - the average number of processes sitting in the ready queue waiting their turn to get into the CPU. Reported in 1-minute, 5-minute, and 15-minute averages by "uptime" and "who".

- Response time - the time taken in an interactive program from the issuance of a command to the commence of a response to that command.

Sometimes it is most desirable to minimize the variance of a criteria than the actual value. I.e. users are more accepting of a consistent predictable system than an inconsistent one, even if it is a little bit slower.

Scheduling algorithm

First-Come-First-Serve Scheduling, FCFS

- FCFS is very simple, just a FIFO queue, like customer waiting in a line at the bank or the ost office or at a copying maching

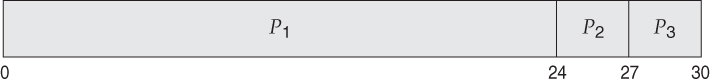

- Unfortunately, however, FCFs can yield some very long average wait times, particularly if the first process to get there takes a long time. For example, consider the following three processes:

| Process | Burst Time |

|---|---|

| P1 | 24 |

| P2 | 3 |

| P3 | 3 |

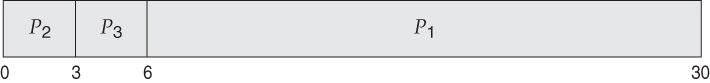

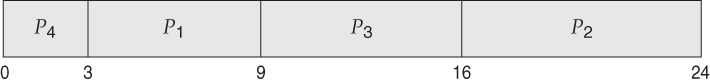

- In the first Gantt chart below, process P1 arrives first. The average waiting time for the three processes is ( 0 + 24 + 27 ) / 3 = 17.0 ms.

- In the second Gantt chart below, the same three processes have an average wait time of ( 0 + 3 + 6 ) / 3 = 3.0 ms. The total run time for the three bursts is the same, but in the second case two of the three finish much quicker, and the other process is only delayed by a short amount.

FCFS can also block the system in a busy dynamic system in another way, known as the convoy effect. When one CPU intensive process blocks the CPU, a number of I/O intensive processes can get backed up behind it, leaving the I/O devices idle. When the CPU hog finally relinquishes the CPU, then the I/O processes pass through the CPU quickly, leaving the CPU idle while everyone queues up for I/O, and then the cycle repeats itself when the CPU intensive process gets back to the ready queue.

Shortest-Job-First Scheduling, SJF

The idea behind the SJF algorithm is to pick the quickest fastest little jb that needs to be done, get it out of the way first, and the pick the next smallest fastest job to do next. Technically, this algorithm picks a process based on the next shortest CPU burst, not the overall process time.

| Process | Burst Time |

|---|---|

| P1 | 6 |

| P2 | 8 |

| P3 | 7 |

| P4 | 3 |

In the case above the average wait time is ( 0 + 3 + 9 + 16 ) / 4 = 7.0 ms, ( as opposed to 10.25 ms for FCFS for the same processes. )

SJF can be proven to be the fastest scheduling algorithm, but it suffers from one important problem: How do you know how long the next CPU burst is going to be?

- For long-term batch jobs this can be done based upon the limits that users set for their jobs when they submit them, which encourages them to set low limits, but risks their having to re-submit the job if they set the limit too low. However that does not work for short-term CPU scheduling on an interactive system.

- Another option would be to statistically measure the run time characteristics of jobs, particularly if the same tasks are run repeatedly and predictably. But once again that really isn't a viable option for short term CPU scheduling in the real world.

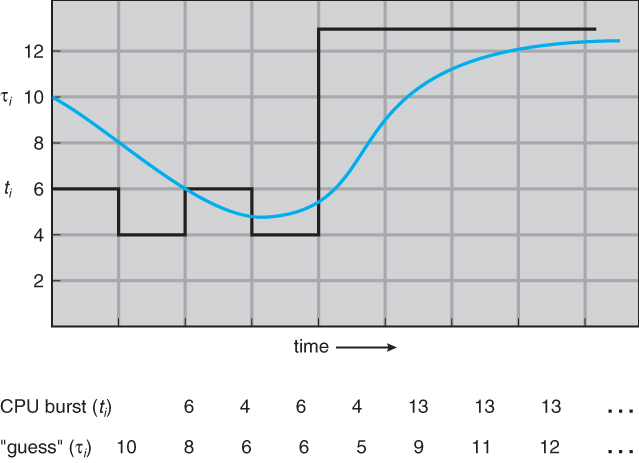

- A more practical approach is to predict the length of the next burst, based on some historical measurement of recent burst times for this process. One simple, fast, and relatively accurate method is the exponential average, which can be defined as follows.

- In this scheme the previous estimate contains the history of all previous times, and alpha serves as a weighting factor for the relative importance of recent data versus past history. If alpha is 1.0, then past history is ignored, and we assume the next burst will be the same length as the last burst. If alpha is 0.0, then all measured burst times are ignored, and we just assume a constant burst time. Most commonly alpha is set at 0.5, as shown below:

- SJF can be either preemptive or non-preemptive. Preemption occurs when a new process arrives in the ready queue that has a predicted burst time shorter than the time remaining in the process whose burst is currently on the CPU. Preemptive SJF is sometimes referred to as shortest remaining time first scheduling.

| Process | Arrival Time | Burst Time |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | 0 | 8 |

| P2 | 1 | 4 |

| P3 | 2 | 9 |

| P4 | 3 | 5 |

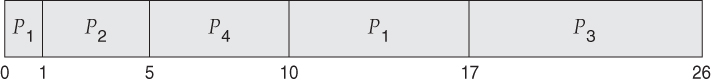

The average wait time in this case is ( ( 5 - 3 ) + ( 10 - 1 ) + ( 17 - 2 ) ) / 4 = 26 / 4 = 6.5 ms. ( As opposed to 7.75 ms for non-preemptive SJF or 8.75 for FCFS. )

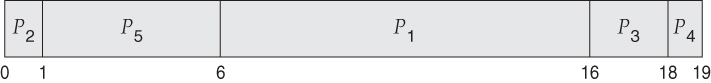

Priority Scheduling

Priority scheduling is a more general case of SJF, in which each job is assigned a priority and the job with the highest priority will get scheduled first. (SJF uses the inverse of the next expected burst time as its priority, the smaller the expected burst time, the higher the priority)

Note that in practice, priorities are implemented using integers within a fixed range, but there is no agreed-upon convention as to whether "high" priorities use large numbers or small numbers. This book uses low number for high priorities, with 0 being the highest possible priority.

Example:

| Process | Burst Time | Priority |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | 10 | 3 |

| P2 | 1 | 1 |

| P3 | 2 | 4 |

| P4 | 1 | 5 |

| P5 | 5 | 2 |

Priorities can be assigned either internally or externally. Internal priorities are assigned by the OS using criteria such as average burst time, ratio of CPU to I/O activity, system resource use, and other factors are available to the kernel. External priorities assigned by users, based on the importance of the job, fees paid, politics, etc.

Priority scheduling can be either preemptive or non-preemptive.

Priority scheduling can suffer from a major problem known as indefinite blocking or starvation, in which a low-priority task can wait forever because there are always some other jobs around that have higher priority.

- if this problem is allowed to occur, then processes will either run eventually when the system load lightens or will eventually get lost when the system is shut down or crashes.

- one common solution to this problem is aging, in which priorities of jobs increase (so the priority number will reduce) the longer they wait. Under this scheme a low-priority job will eventually get its priority raised high enough that it gets run.

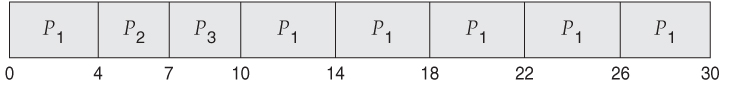

Round Robin Scheduling

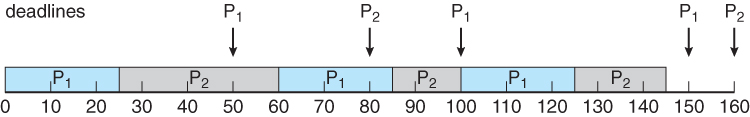

This type of scheduling is similar to FCFS scheduling, except that CPU bursts are assigned with limits called time quantum.

When a process is given the CPU, a timer is set for whatever value has been set for a time quantum.

- if the process finished its burst before the time quantum timer expires, then it is swapped out of the CPU just like the normal FCFS algorithm. If the timer goes off first, then the process is swapped out of the CPU and moved to the back end of the ready queue.

- The ready queue is maintained as a circular queue, so when all processes have had a turn, then the scheduler gives the first process another turn and so on.

- RR scheduling can give the effect of all processors sharing the CPU equally, although the average wait time can be longer than with other scheduling algorithms. In the following example the average wait time is 5.66 ms.

| Process | Burst Time |

|---|---|

| P1 | 24 |

| P2 | 3 |

| P3 | 3 |

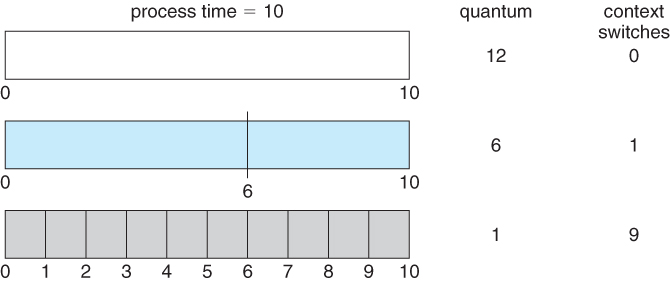

The performance of RR is sensitive to the time quantum selected. If the quantum is large enough, then RR reduces to the FCFS algorithm; If it is very small, then each process gets 1/nth of the processor time and share the CPU equally.

BUT, a real system invokes overhead for every context switch, and the smaller the time quantum the more context switches there are. Most modern systems use time quantum between 10 and 100 milliseconds, and context switch times on the order of 10 microseconds, so the overhead is small relative to the time quantum.

Turn around time also varies with quantum time, in a non-apparent manner. In general, turnaround time is minimized if most processes finish their next cpu burst within one time quantum. For example, with three processes of 10 ms bursts each, the average turnaround time for 1 ms quantum is 29, and for 10 ms quantum it reduces to 20. However, if it is made too large, then RR just degenerates to FCFS. A rule of thumb is that 80% of CPU bursts should be smaller than the time quantum.

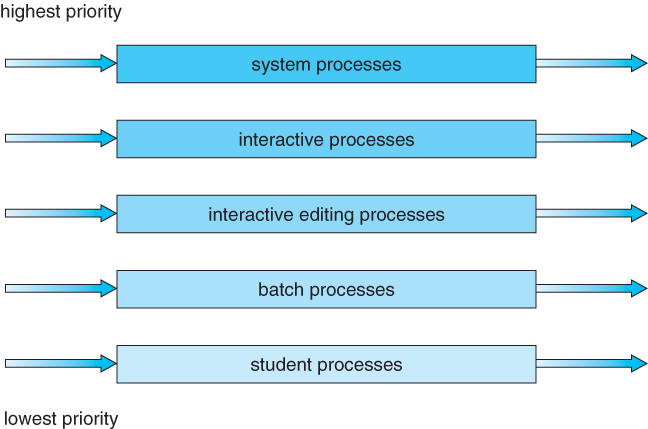

Multilevel Queue Scheduling

When processes can be readily categorized, then multiple separate queues can be established, each implementing whatever scheduling algorithm is most appropriate for that type of job, and/or with different parametric adjustments.

Scheduling must also be done between queues, that is scheduling one queue to get time relative to other queues. Two common options are strict priority ( no job in a lower priority queue runs until all higher priority queues are empty ) and round-robin ( each queue gets a time slice in turn, possibly of different sizes. )

Note that under this algorithm jobs cannot switch from queue to queue - Once they are assigned a queue, that is their queue until they finish.

Multilevel Feedback-Queue Scheduling

Multilevel feedback queue scheduling is similar to the ordinary multilevel queue scheduling described above, except jobs may be moved from one queue to another for a variety of reasons:

- If the characteristics of a job change between CPU-intensive and I/O intensive, then it may be appropriate to switch a job from one queue to another.

- Aging can also be incorporated, so that a job that has waited for a long time can get bumped up into a higher priority queue for a while.

Multilevel feedback queue scheduling is the most flexible, because it can be tuned for any situation. But it is also the most complex to implement because of all the adjustable parameters. Some of the parameters which define one of these systems include:

- the number of queues

- the scheduling algorithm for each queue

- the methods used to upgrade or demote processes from one queue to another.

- The method used to determine which queue a process enters initially.

Thread Scheduling

The process scheduler schedules only the kernel threads. User threads are mapped to kernel threads by the thread library. The OS (and in particular the scheduler) is unaware of them.

Contention Scope

Contention scope refers to the scope in which threads compete for the use of physical CPUs. On systems implementing many-to-one and many-to-many threads, Process Contention Scope, PCS, occurs, because competition occurs between threads that are part of the same process. ( This is the management / scheduling of multiple user threads on a single kernel thread, and is managed by the thread library. )

System Contention Scope, SCS, involves the system scheduler scheduling kernel threads to run on one or more CPUs. Systems implementing one-to-one threads ( XP, Solaris 9, Linux ), use only SCS.

PCS scheduling is typically done with priority, where the programmer can set and/or change the priority of threads created by his or her programs. Even time slicing is not guaranteed among threads of equal priority.

Real-Time CPU Scheduling

Real-time systems are those in which the time at which tasks complete is crucial to their performance

- Soft real-time systems have degraded performance if their timing needs cannot be met. Example: streaming video.

- Hard real-time systems have total failure if their timing needs cannot be met. Examples: Assembly line robotics, automobile air-bag deployment.

Minimizing latency

Event Latency is the time between the occurrence of a triggering event and the ( completion of ) the system's response to the event.

In addition to the time it takes to actually process the event, there are two additional steps that must occur before the event handler ( Interrupt Service Routine, ISR ), can even start:

- Interrupt processing determines which interrupt(s) have occurred, and which interrupt handler routine to run. In the event of simultaneous interrupts, a priority scheme is needed to determine which ISR has the highest priority and gets to go next.

- Context switching involves removing a running process from the CPU, saving its state, and loading up the ISR so that it can run.

Priority-Based Scheduling

Real-time systems require pre-emptive priority-based scheduling systems. Soft real-time systems do the best they can, but make no guarantees. They are generally discussed elsewhere. Hard real-time systems, described here, must be able to provide firm guarantees that a tasks scheduling needs can be met.

- One technique is to use a admission-control algorithm, in which each task must specify its needs at the time it attempts to launch, and the system will only launch the task if it can guarantee that its needs can be met.

Hard real-time systems are often characterized by tasks that must run at regular periodic intervals, each having a period p, a constant time required to execute, ( CPU burst ), t, and a deadline after the beginning of each period by which the task must be completed, d. In all cases, t <= d <= p.

Rate-Monotonic Scheduling

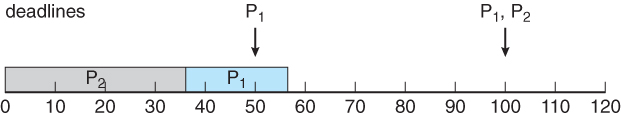

The rate-monotonic scheduling algorithm uses pre-emptive scheduling with static priorities. Priorities are assigned inversely to the period of each task, giving higher ( better ) priority to tasks with shorter periods. Let's consider an example, first showing what can happen if the task with the longer period is given higher priority:

- Suppose that process P1 has a period of 50, an execution time of 20, and a deadline that matches its period ( 50 ).

- Similarly suppose that process P2 has period 100, execution time of 35, and deadline of 100.

- The total CPU utilization time is 20 / 50 = 0.4 for P1, and 25 / 100 = 0.35 for P2, or 0.75 ( 75% ) overall.

- However if P2 is allowed to go first, then P1 cannot complete before its deadline:

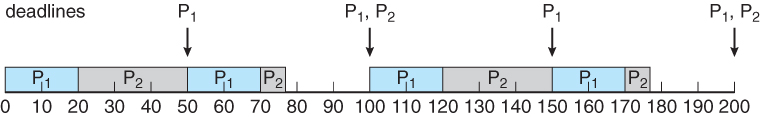

- Now on the other hand, if P1 is given higher priority, it gets to go first, and P2 starts after P1 completes its burst.

- At time 50 when the next period for P1 starts, P2 has only completed 30 of its 35 needed time units, but it gets pre-empted by P1.

- At time 70, P1 completes its task for its second period, and the P2 is allowed to complete its last 5 time units.

- Overall both processes complete at time 75, and the cpu is then idle for 25 time units, before the process repeats.

Rate-monotonic scheduling is considered optimal among algorithms that use static priorities, because any set of processes that cannot be scheduled with this algorithm cannot be scheduled with any other static-priority scheduling algorithm either. There are, however, some sets of processes that cannot be scheduled with static priorities.

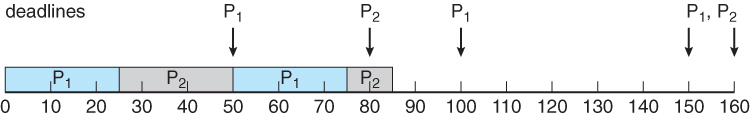

- For example, supposing that P1 =50, T1 = 25, P2 = 80, T2 = 35, and the deadlines match the periods.

- Overall CPU usage is 25/50 = 0.5 for P1, 35 / 80 =0.44 for P2, or 0.94 ( 94% ) overall, indicating it should be possible to schedule the processes.

- With rate-monotonic scheduling, P1 goes first, and completes its first burst at time 25.

- P2 goes next, and completes 25 out of its 35 time units before it gets pre-empted by P1 at time 50.

- P1 completes its second burst at 75, and then P2 completes its last 10 time units at time 85, missing its deadline of 80 by 5 time units.

- The worst-case CPU utilization for scheduling N processes under this algorithm is N * ( 2^(1/N) - 1 ), which is 100% for a single process, but drops to 75% for two processes and to 69% as N approaches infinity. Note that in our example above 94% is higher than 75%.

Earliest-Deadline-First Scheduling

Earliest Deadline First ( EDF ) scheduling varies priorities dynamically, giving the highest priority to the process with the earliest deadline.

Here's an example: At time 0 P1 has the earliest deadline, highest priority, and goes first., followed by P2 at time 25 when P1 completes its first burst. At time 50 process P1 begins its second period, but since P2 has a deadline of 80 and the deadline for P1 is not until 100, P2 is allowed to stay on the CPU and complete its burst, which it does at time 60. P1 then starts its second burst, which it completes at time 85. P2 started its second period at time 80, but since P1 had an earlier deadline, P2 did not pre-empt P1. P2 starts its second burst at time 85, and continues until time 100, at which time P1 starts its third period. At this point P1 has a deadline of 150 and P2 has a deadline of 160, so P1 preempts P2. P1 completes its third burst at time 125, at which time P2 starts, completing its third burst at time 145. The CPU sits idle for 5 time units, until P1 starts its next period at 150 and P2 at 160.

- Question: Which process will get to run at time 160, and why?

- Answer: Process P2, because P1 now has a deadline of 200 and P2's new deadline is 240.