Process Synchronization

The Critical Section Problem

The general idea is that in a number of cooperating processes, each has a critical section of code, with the following conditions and terminologies:

- only one process in the group can be allowed to execute in their critical section at any one time. If one process is already executing their critical section and another process wishes to do so, then the second process must be made to wait until the first process has completed their critical section work

- the code preceding the critical section, and which controls access to the critical section, is termed the entry section. It acts like a carefully controlled locking door

- the code following the critical section is termed the exit section. It generally releases the lock on someone elses door, or at least lets the world know that they are no longer in their critical section

- the rest of the code not included in either the critical section or the entry or exit sections is termed the remainder section

do {//entry sectioncritical section// exit sectionremainder section} while (TRUE);}

A solution to the critical section problem must satisfy the following three conditions:

- Mutual Exclusion - Only one process at a time can be executing in their critical section

- Progress - If no process is currently executing in their critical section, and one or more processes want to execute their critical section, then only the processes not in their remainder sections car participate in the decision, and the decision cannot be postponed indefinitely. (Processes cannot be blocked forever waiting to get into their critical sections)

- Bounded Waiting - there exists a limit as to how many other processes can get into their critical sections after a process requests entry into their critical section and before that request is granted.

Kernel processes can also be subject to race conditions, which can be especially problematic when updating commonly shared kernel data structures such as open file tables or virtual memory management. Accordingly kernels can take on one of two forms:

- Non-preemptive kernels do not allow processes to be interrupted while in kernel mode. This eliminates the possibility of kernel-mode race conditions, but requires kernel mode operations to complete very quickly, and can be problematic for real-time systems, because timing cannot be guaranteed.

- Preemptive kernels allow for real-time operations, but must be carefully written to avoid race conditions. This can be especially tricky on SMP systems, in which multiple kernel processes may be running simultaneously on different processors.

A race condition is an undesirable situation that occurs when a device or system attempts to perform two or more operations at the same time, but because of the nature of the device or system, the operations must be done in the proper sequence to be done correctly.

Peterson's Solution

Peterson's Solution is a classic software-based solution to the critical section problem. It is unfortunately not guaranteed to work on modern hardware, but it illustrates a number of important concepts.

Peterson's solution is based on two shared data items:

int turn- indicates whose turn it is to enter into the critical sectionboolean flag[i]indicates when a process wants to enter their critical section, it sets flag[i] to true.

do {//entry is belowflag [i] = TRUE;turn = j;while (flag[j] && turn == j);critical section//exit is belowflag[i] = FALSE;remainder section} while (TRUE);

To prove that the solution is correct, we must examine the three conditions listed above:

- Mutual exclusion - If one process is executing their critical section when the other wishes to do so, the second process will become blocked by the flag of the first process. IF both processes attempt to enter at the same time, the last process to execute "turn = j" will be blocked.

- Progress - Each process can only be blocked at the while if the other process wants to use the critical section (flag[i] == true), AND it is the process's turn to use the critical section (turn == j). If both of these If both of those conditions are true, then the other process (j) will be allowed to enter the critical section, and upon exiting the critical section, will set flag[j] to false, releasing process i. The shared variable turn assures that only one process at a time can be blocked, and the flag variable allows one process to release the other when exiting their critical section.

- Bounded Waiting - as each process enters their entry section, they set the turn variable to be the other processes turn. Since no process ever sets it back to their own turn, this ensures that each process will have to let the other process go first at most one time before it becomes their turn again.

- Note that the instruction "turn = j" is atomic, that is sit is a single machine instruction which cannot be interrupted.

Synchronization Hardware

- To generalize the solution(s) expressed above, each process when entering their critical section must set some sort of lock, to prevent other processes from entering their critical sections simultaneously, and must release the lock when exiting their critical section, to allow other processes to proceed. Obviously it must be possible to attain the lock sonly when no their process has already set a lock. Specific implementations of this general procedure can get quite complicated, and may include hardware solutions as outlined in this sections.

- One simple solution to the critical section problem is to simply prevent a process from being interrupted while in their critical section, which is the approach taken by non preemptive kernels. Unfortunately this does not work well in multiprocessor environments, due to the difficulties in disabling and the re-enabling interrupts on all processors. There is also a question as to how this approach affects timing if the clock interrupt is disabled.

- Another approach is for hardware to proved certain atomic operations. These operations are guaranteed to operate as a single instruction, without interruption. One such operation is the "Test and Set" which simultaneously sets a boolean lock variable and returns its previous value as shown below:

boolean TestAndSet (boolean *target) {boolean rv = *target;*target = TRUE;return rv;}do {while (TestAndSetLock(&lock)); // do nothing// critical sectionlock = False// remainder section} while (TRUE);

Above is a mutual-exclusion implementation with TestAndSet(). Another variation on the test-and-set is an atomic swap of two booleans as shown below.

int compare_and_swap(int *value, int expected, int new_value) {int temp = *value;if (*value == expected)*value = new_value;return temp;}do {while (compare_and_swap(%loc, 0, 1) != 0); /* do nothing *//* critical section */lock = 0;/* remainder section */} while (true);

- The above examples satisfy the mutual exclusion requirement, but unfortunately do not guarantee bounded waiting. If there are multiple processes trying to get into their critical sections, there is no guarantee of what order they will enter, and any one process could have the bad luck to wait forever until they got their turn in the critical section. ( Since there is no guarantee as to the relative rates of the processes, a very fast process could theoretically release the lock, whip through their remainder section, and re-lock the lock before a slower process got a chance. As more and more processes are involved vying for the same resource, the odds of a slow process getting locked out completely increase. )

Here is a solution that does satisfy the above point

do {waiting[i] = TRUE;key = TRUE;while (waiting[i] && key)key = TestAndSet (&lock);waiting = FALSE'// critical sectionj = (i+1) % n;while ((j != i) && !waiting[j])j = (j+1) % nif (j == i)lock = FALSE;elsewaiting[j] = FALSE;// remainder section} while (TRUE);

- The key feature of the above algorithm is that a process blocks on the AND of the critical section being locked and that this process is in the waiting state. When exiting a critical section, the exiting process does not just unlock the critical section and let the other processes have a free-for-all trying to get in. Rather it first looks in an orderly progression ( starting with the next process on the list ) for a process that has been waiting, and if it finds one, then it releases that particular process from its waiting state, without unlocking the critical section, thereby allowing a specific process into the critical section while continuing to block all the others. Only if there are no other processes currently waiting is the general lock removed, allowing the next process to come along access to the critical section.

- Unfortunately, hardware level locks are especially difficult to implement in multi-processor architectures. Discussion of such issues is left to books on advanced computer architecture.

Mutex Locks

The hardware solutions above are difficult for ordinary programmers to access, particularly on multi-processor machines, and particularly because they are often platform-dependent. Therefore most systems offer a software API equivalent called mutex locks or simply mutexes. (For mutual exclusion). The terminology is to acquire a lock prior to entering a critical section, and to release it when exiting.

Here is a solution to the critical section problem using mutex locks.

do {// acquire lockcritical section// release lockremainder section} while (TRUE);

Just as with hardware locks, the acquire step will block the process if the lock is in use by another process, and both the acquire and release operations are atomic.

Below is how acquire and release are implemented based on a boolean variable available.

// Acquireacquire() {while (!available); /* busy wait */available = false;;}// Releaserelease() {available = true;}

One problem with the implementation shown here, (and in the hardware solutions presented earlier), is the busy loop used to block processes in the acquire phase. These types of locks are referred to as spinlocks, because the CPU just sits and spins while blocking the process. Spinlocks are very inefficient and waste CPU cycles on single-CPU single-threaded machines. However, they are good for multi-threaded machines.

Semaphores

A more robust alternative to simple mutexes is to use semaphores, which are integer variables for which only two (atomic) operations are defined, the wait and signal operations, as shown in the following figure.

Semaphores are comprised of two operations shown below:

// Waitwait (S) {while S <= 0; // no-opS--;}// Signalsignal (S) {S++;}

Semaphore Usage

In practice, semaphores can take on one of two forms:

- Binary semaphores can take on of two values, 0 or 1. They can be used to solve the critical section problem as described above, and can be used as mutexes on systems that do not provide a separate mutex mechanism. The general structure is shown below:

do {waiting(mutex);// critical sectionsignal (mutex);// remainder section} while (TRUE);

- Counting semaphores can take on any integer value, and are usually used to count the number remaining of some limited resource. The counter is initialized to the number of such resources available in the system, and whenever the counting semaphore is greater than zero, then a process can enter a critical section and use one of the resources. When the counter gets to zero (or negative in some implementations), then the process blocks until another process frees up a resource and increments the counting semaphore with a signal call.

Semaphores can also be used to synchronize certain operations between processes. For examples, suppose it is import that process P1 executes statement S1 before process P2 executes statement S2.

- First we create a semaphore named

synchthat is shared by the two processes and initialize it as zero. - Then in process P1 we insert the code:S1;signal (synch);

- and in process P2 we insert the code:wait (synch);S2;

- Because

synchwas initialized to 0, process P2 will block on the wait until after P1 executes the call to signal.

Semaphore implementation

The big problem with semaphores as described above is the busy loop in the wait call, which consumes CPU cycles with doing any useful work.

An alternative approach is to block a process when it is forced to wait for an available semaphore, and sway it out of the CPU. In this implementation each semaphore needs to maintain a list of processes that are blocked waiting for it, so that one of the processes can be woken up and swapped back in when the semaphore becomes available.

The new definition of a semaphore is as follows:

// Semaphore Structure:typedef struct {int value;struct process *list;} semaphore;// Wait Operation:wait (semaphore *S) {S -> value--;if (S -> value < 0) {add this process to S -> list;block();}}// Signal Operation:signal(semaphore *S) {S -> value++;if (S -> value <= 0) {remove a process P from S->list;wakeup(P);}}

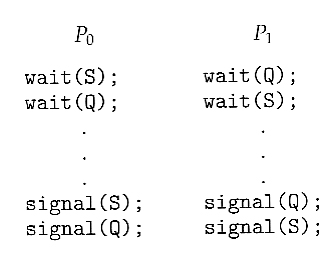

Deadlocks and starvation

One important problem that can arise when using semaphores to block processes waiting for a limited resource is the problem of deadlocks, which occur when multiple processes are blocked, each waiting for a resource that can only be freed by one of the other ( blocked ) processes.

Another problem to consider is that of starvation, in which one or more processes gets blocked forever, and never get a chance to take their turn in the critical section. For example, in the semaphores above, we did not specify the algorithms for adding processes to the waiting queue in the semaphore in the wait( ) call, or selecting one to be removed from the queue in the signal( ) call. If the method chosen is a FIFO queue, then every process will eventually get their turn, but if a LIFO queue is implemented instead, then the first process to start waiting could starve.

Priority Inversion

A challenging scheduling problem arises when a high-priority process gets blocked waiting for a resource that is currently held by a low-priority process.

If the low-priority process gets pre-empted by one or more medium-priority processes, then the high-priority process is essentially made to wait for the medium priority processes to finish before the low-priority process can release the needed resource, causing a priority inversion. If there are enough medium-priority processes, then the high-priority process may be forced to wait for a very long time.

One solution is a priority-inheritance protocol, in which a low-priority process holding a resource for which a high-priority process is waiting will temporarily inherit the high priority from the waiting process. This prevents the medium-priority processes from preempting the low-priority process until it releases the resource, blocking the priority inversion problem.

Classic Problems of Synchronization

Bounded-Buffer Problem

This is a generalization o the producer-consumer problem wherein access is controlled to a shared group of buffers in a limited size.

In this solution, the two counting semaphores "full" and "empty" keep track of the current number of full and empty buffers respectively (and initialized to 0 and N respectively). The binary semaphore mutex controls access to the critical section. The producer and consumer processes are nearly identical - one can think of the producer as producing full buffers, and the consumer producing empty buffers.

Producer process:

do {...// produce an item in nextp...wait(empty);wait(mutex);...// add nextp to buffer...signal (mutex);signal (full);} while(TRUE);

Consumer process:

do {wait (full);wait (mutex);...// remove an item from buffer to nextc...signal (mutex);signal (empty);...// consume the item in nextc...} while (TRUE);

The Readers-Writers Problem

In the readers-writers problem there are some processes ( termed readers ) who only read the shared data, and never change it, and there are other processes ( termed writers ) who may change the data in addition to or instead of reading it. There is no limit to how many readers can access the data simultaneously, but when a writer accesses the data, it needs exclusive access.

There are several variations to the readers-writers problem, most centered around relative priorities of readers versus writers.

- The first readers-writers problem gives priority to readers. In this problem, if a reader wants access to the data, and there is not already a writer accessing it, then access is granted to the reader. A solution to this problem can lead to starvation of the writers, as there could always be more readers coming along to access the data. ( A steady stream of readers will jump ahead of waiting writers as long as there is currently already another reader accessing the data, because the writer is forced to wait until the data is idle, which may never happen if there are enough readers. )

- The second readers-writers problem gives priority to the writers. In this problem, when a writer wants access to the data it jumps to the head of the queue - All waiting readers are blocked, and the writer gets access to the data as soon as it becomes available. In this solution the readers may be starved by a steady stream of writers.

The following code is an example of the first readers-writers problem, and involves an important counter and two binary semaphores:

readcountis used by the reader processes, to count the number of readers currently accessing the data.mutexis a semaphore used only by the readers for controlled access toreadcount.rw_mutexis a semaphore used to block and release the writers. The first reader to access the data will set this lock and the last reader to exit will release it; The remaining readers do not touchrw_mutex. ( Eighth edition called this variable wrt. )- Note that the first reader to come along will block on

rw_mutexif there is currently a writer accessing the data, and that all following readers will only block onmutexfor their turn to incrementreadcount.

Writer process:

do {wait(rw_mutex);...// writing is performed...signal (rw_mutex);} while (true);

Reader process:

do {wait(mutex);read_count++;if (read_count == 1)wait(rw_mutex);signal(mutex);...// reading is performed...wait(mutex);read_count--;if (read_count == 0)signal(rw_mutex);signal(mutex);} while (true);

The Dining-Philosophers Problem

The dining philosophers problem involving the allocation of limited resources amongst a group of process in a deadlock-fre and starvation-free manner:

- Consider five philosophers sitting around a table, in which there are five chopsticks evenly distributed and an endless bowl of rice in the center, as shown in the diagram below. ( There is exactly one chopstick between each pair of dining philosophers. )

- These philosophers spend their lives alternating between two activities: eating and thinking.

- When it is time for a philosopher to eat, it must first acquire two chopsticks - one from their left and one from their right.

- When a philosopher thinks, it puts down both chopsticks in their original locations.

One possible solution, as shown in the following code section, is to use a set of five semaphores ( chopsticks[ 5 ] ), and to have each hungry philosopher first wait on their left chopstick ( chopsticks[ i ] ), and then wait on their right chopstick ( chopsticks[ ( i + 1 ) % 5 ] )

But suppose that all five philosophers get hungry at the same time, and each starts by picking up their left chopstick. They then look for their right chopstick, but because it is unavailable, they wait for it, forever, and eventually all the philosophers starve due to the resulting deadlock.

The structure of philosopher i:

do {wait (chopstick[i]);wait (chopstick[(i+1) % 5]);...// eat...signal(chopstick[i]);signal(chopstick[(i+1)] % 5);...// think} while (TRUE);

Some potential solutions to the problem include:

- Only allow four philosophers to dine at the same time. ( Limited simultaneous processes. )

- Allow philosophers to pick up chopsticks only when both are available, in a critical section. ( All or nothing allocation of critical resources. )

- Use an asymmetric solution, in which odd philosophers pick up their left chopstick first and even philosophers pick up their right chopstick first. ( Will this solution always work? What if there are an even number of philosophers? )

Monitors

Semaphores can be very useful for concurrency problems if used correctly. A higher-level language construct is developed called monitors.

Monitor Usage

A monitor is essentially a class, in which all data is private, and with the special restriction that only one method within any given monitor object may be active at the same time. An additional restriction is that monitor methods may only access the shared data within the monitor and any data passed to them as parameters. I.e. they cannot access any data external to the monitor.

monitor monitor_name {// shared variable declarationsprocedure P1 (...) {}procedure P1 (...) {}...procedure Pn (...) {}initialization code (...) {}}

In order to fully realize the potential of monitors, we need to introduce one additional new data type, known as a condition.

- A variable of type condition has only two legal operations, wait and signal. I.e. if X was defined as type condition, then legal operations would be X.wait( ) and X.signal( )

- The wait operation blocks a process until some other process calls signal, and adds the blocked process onto a list associated with that condition.

- The signal process does nothing if there are no processes waiting on that condition. Otherwise it wakes up exactly one process from the condition's list of waiting processes. ( Contrast this with counting semaphores, which always affect the semaphore on a signal call. )

But now there is a potential problem - If process P within the monitor issues a signal that would wake up process Q also within the monitor, then there would be two processes running simultaneously within the monitor, violating the exclusion requirement. Accordingly there are two possible solutions to this dilemma:

- Signal and wait - When process P issues the signal to wake up process Q, P then waits, either for Q to leave the monitor or on some other condition.

- Signal and continue - When P issues the signal, Q waits, either for P to exit the monitor or for some other condition.

- There are arguments for and against either choice. Concurrent Pascal offers a third alternative - The signal call causes the signaling process to immediately exit the monitor, so that the waiting process can then wake up and proceed.

Dining-Philosophers Solution Using Monitors

This solution to the dining philosophers uses monitors, and the restriction that a philosopher may only pick up chopsticks when both are available. There are also two key data structures in use in this solution:

enum { THINKING, HUNGRY,EATING } state[ 5 ];A philosopher may only set their state to eating when neither of their adjacent neighbors is eating.( state[ ( i + 1 ) % 5 ] != EATING && state[ ( i + 4 ) % 5 ] != EATING ).condition self[ 5 ];This condition is used to delay a hungry philosopher who is unable to acquire chopsticks.

In the following solution philosophers share a monitor, DiningPhilosophers, and eat using the following sequence of operations:

- DiningPhilosophers.pickup( ) - Acquires chopsticks, which may block the process.

- eat

- DiningPhilosophers.putdown( ) - Releases the chopsticks.

monitor DiningPhilosophers{enum {THINKING, HUNGRY, EATING} state[5];condition self[5];void pickup(int i) {state[i] = HUNGRY;test(i);if (state[i] != EATING)self[i].wait();}void putdown(int i) {state[i] = THINKING;test((i + 4) % 5);test((i + 1) % 5);}void test (int i) {if ((state[(i+4) % 5] != EATING) && (state[i] == HUNGRY) && state[[i + 1] % 5] != EATING) {state[i] = EATING;self[i].signal();}}initialization_code() {for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++)state[i] = THINKING;}}

Implementing a Monitor Using Semaphores

One possible implementation of a monitor uses a semaphore "mutex" to control mutual exclusionary access to the monitor, and a counting semaphore "next" on which processes can suspend themselves after they are already "inside" the monitor ( in conjunction with condition variables, see below. ) The integer next_count keeps track of how many processes are waiting in the next queue. Externally accessible monitor processes are then implemented as:

wait (mutex);...body of F...if (next_count > 0)signal(next);elsesignal(mutex);

Condition variables can be implemented using semaphores as well. For a condition x, a semaphore "x_sem" and an integer "x_count" are introduced, both initialized to zero. The wait and signal methods are then implemented as follows. (This approach to the condition implements the signal-and-wait option described above for ensuring that only one process at a time is active inside the monitor.)

//Wait:x_count++;if (nex_count > 0)signal_next;elsesignal_next;wait(x_sem);x_count--;//Signal:if (x_count > 0) {next_count++;signal(x_sem);wait(next);next_count--;}

Resuming Processes Within a Monitor

When there are multiple processes waiting on the same condition within a monitor, how does one decide which one to wake up in response to a signal on that condition? One obvious approach is FCFS, and this may be suitable in many cases.

Another alternative is to assign ( integer ) priorities, and to wake up the process with the smallest ( best ) priority.

The following illustrates the use of such a condition within a monitor used for resource allocation. Processes wishing to access this resource must specify the time they expect to use it using the acquire( time ) method, and must call the release( ) method when they are done with the resource.

monitor ResourceAllocator{boolean busy;condition x;void acquire(int time) {if (busy)x.wait(time);busy = TRUE;}void release() {busy = FALSE;x.signal();}initialization_code() {busy = FALSE;}}

Unfortunately the use of monitors to restrict access to resources still only works if programmers make the requisite acquire and release calls properly. One option would be to place the resource allocation code into the monitor, thereby eliminating the option for programmers to bypass or ignore the monitor, but then that would substitute the monitor's scheduling algorithms for whatever other scheduling algorithms may have been chosen for that particular resource.