Processes

Process Concept

A process is an instance of a program in execution. Batch systems work in terms of "jobs". Many modern process concepts are still expressed in terms of jobs, (e.g. job scheduling), and the two terms are often used interchangeably.

The Process

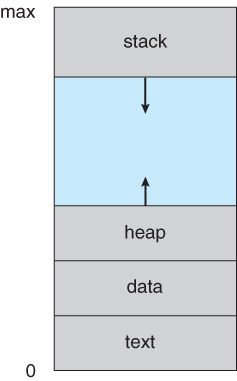

- Process memory is divided into four sections as shown below:

- The text section comprises the compiled program code, read in from non-volatile storage when the program is launched.

- The data section stores global and static variables, allocated and initialized prior to executing main.

- The heap is used for dynamic memory allocation, and is managed via calls to new, delete, malloc, free, etc.

- The stack is used for local variables. Space on the stack is reserved for local variables when they are declared ( at function entrance or elsewhere, depending on the language ), and the space is freed up when the variables go out of scope. Note that the stack is also used for function return values, and the exact mechanisms of stack management may be language specific.

- Note that the stack and the heap start at opposite ends of the process's free space and grow towards each other. If they should ever meet, then either a stack overflow error will occur, or else a call to new or malloc will fail due to insufficient memory available.

- When processes are swapped out of memory and later restored, additional information must also be stored and restored. Key among them are the program counter and the value of all program registers.

Process State

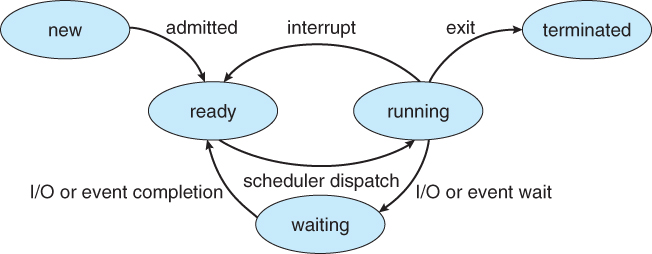

Processes may be in one of 5 states, as shown below.

- New - The process is in the stage of being created.

- Ready - The process has all the resources available that it needs to run, but the CPU is not currently working on this process's instructions.

- Running - The CPU is working on this process's instructions.

- Waiting - The process cannot run at the moment, because it is waiting for some resource to become available or for some event to occur. For example the process may be waiting for keyboard input, disk access request, inter-process messages, a timer to go off, or a child process to finish.

- Terminated - The process has completed.

Process Control Block

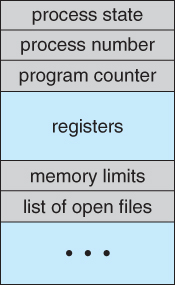

For each process there is a PCB which stores the following process-specific information.

- Process State - as discussed above

- Process ID and parent process ID

- CPU registers and Program Counter - These need to be saved and restored when swapping processes in and out of the CPU

- CPU-Scheduling information - Such as priority information and pointers to scheduling queues

- Memory-management information - E.g. page tables or segment tables

- Accounting information - user and kernel CPU time consumer, account numbers, limits, etc.

- I/O Status information - Device allocated, open file tables.

Threads

Modern systems allow a single process to have multiple threads of executions, which execute concurrently.

Process Scheduling

The two main objectives of the process scheduling system are to keep the CPU busy at all times and to deliver "acceptable" response times for all programs, particularly for interactive ones.

Scheduling Queues

- All processes are stored in the job queue

- Processes in the Ready state are placed in the ready queue

- Processes waiting for a device are placed in device queues

- There is a separate device queue for each device

Schedulers

A long-term scheduler is mostly found in batch systems or heavily loaded systems. It runs infrequently and can afford to take the time to implement intelligent and advanced scheduling algorithms.

The short-term scheduler, or a CPU scheduler, runs very frequently, on the order of 100 milliseconds, and must very quickly swap one process out of the CPU and swap in another one.

Some systems employ a medium-term scheduler. When system loads get high, this scheduler will swap one or more processes out of the ready queue system for a few seconds, in order to allow smaller faster jobs to finish up quickly and clear the system.

An efficient scheduling system will select a good process mix of CPU-bound processes and I/O bound processes.

Context Switch

Whenever an interrupt arrives, the CPU must do a state-save of the currently running process, then switch into kernel mode to handle the interrupt, and then do a state-restore of the interrupted process.

Similarly, a context switch occurs when the time slice for one process has expired and a new process is to be loaded from the ready queue. This will be started by a timer interrupts, which will then cause the current process' state to be saved and the new process' state to be restored.

Saving and restoring states involves saving and restoring all of the registers and program counter(s), as well ass the process control blocks described above.

Context switches happens very frequently, and the overhead of doing the switching is lost CPU time, so context switches must be as fast as possible.

Operations on Process

Process Creation

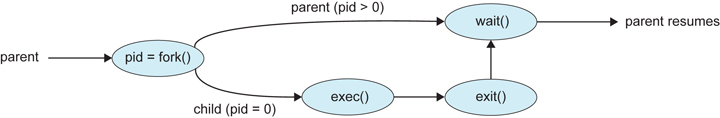

- Processes may create other processes through appropriate system calls such as fork or spawn. The process which does the creating is called parent and the other is termed the child.

- Each process is given an integer identifier, termed its process identifier or PID. The parent PID is also stored for each process.

- On typical UNIX systems the process scheduler is termed sched, and is given

PID 0. The first thing it does at system startup time is to launch init, which gives that processPID 1. Init then launches all system daemons (computer program that runs as a background process) and user logins, and becomes the ultimate parent of all other processes. - A child process may receive some amount of shared resources from the parent. A limit of resources can be placed by the parent, so the children don't consume too many resources

- There are two options for the parent process after creating the child

- Wait for the child process to terminate. The parent makes a

wait()system call, for either a specific child or any child that causes the parent process to block until thewait()returns. UNIX shells normally wait for their children to complete before issuing a new prompt. - Run concurrently with the child. This is the operation seen when a UNIX shell runs a process as a background task It is also possible for the parent to run for a while, and then wait for the child later.

- Wait for the child process to terminate. The parent makes a

- Two possibilities for the address space of the child relative to the parent:

- The child may be an exact duplicate of the parent. Same program and data segments in memory. Each will have their own PCB, including program counter, registers and PID. This is known as the

fork()system call in UNIX. - The child process may have a new program loaded into its address space, with all new code and data segments. This is known as the

spawn()system call in Windows. UNIX systems implement a second step using theexec()system call.

- The child may be an exact duplicate of the parent. Same program and data segments in memory. Each will have their own PCB, including program counter, registers and PID. This is known as the

Here is an example of a fork():

#include <sys/types.h>#include <stdio.h>#include <unistd.h>int main(){pid_t pid;/* fork a child process */pid = fork();if (pid < 0) /* error occurred */ {fprintf (stderr, "Fork Failed");exit(-1);}else if (pid == 0) /* child process */ {execlp ("/bin/ls", "ls", NULL);}else {/* parent process *//* parent will wait for child to complete */wait(NULL);printf("Child Complete");exit(0);}}

Process creation using the fork() system call:

Process Termination

- Processes may request their own termination by making the

exit()system call, typically returning an int. This is passed to the parent if it is doing a `wait(), and is typically 0 on successful completion and some non-zero if there are problems.- child code:int exitCode;exit ( exitCode ) // return the exitCode; has the same effect when executed from main()

- parent code:pid_t pid;int statuspid = wait( &status );// pid indicates which child exited. exitCode in low-order bits of status// macros can test the high-order bits of status for why it stopped

- child code:

- Process may also be terminated by the system for the following reasons:

- the inability of the system to deliver necessary system resources

- in response to a KILL command, or other un handled process interrupt

- if the parent exits, the system may or may not allow the child to continue without a parent. (On UNIX, orphan processes are generally inherited by init, which proceeds to kill them. The UNIX

nohupcommand allows a child to continue executing after its parent has exited.)

- when a process terminates, all of its processes are freed up. The process termination time and status are returned to the parent if the parent is waiting for the child to terminate, or eventually return to init if the process becomes an orphan. *Processes that are trying to terminate, but which cannot because their parent is not waiting for them are termed zombies*. These are eventually inherited by init as orphans and killed.

Interprocess Communication

- Independent Processes operating concurrently on a system are those that neither affect other processes or be affected by other processes

- Cooperative Processes are those that can affect or be affected by other processes. There are several reasons why cooperating processes are allowed:

- Information Sharing: processes might need to access the same file (pipelines)

- Computation speedup: processes are broken down into subtasks

- Modularity: system is used like cooperating modules (client-server architecture)

- Convenience: a single user may be multitasking

- Co-operating processes require some type of inter-process communication, which is most commonly one of two types: Shared Memory systems or Message Passing systems

Shared Memory is faster once it is setup, because no system calls are required and access occurs at normal memory speeds. However, its complicated to setup and doesn't work across multiple computers. It's preferable when large amounts of information must be shared quickly on the same computer.

Message Passing requires system calls for every message transfer, and therefore slower. Simple to setup and works on multiple computer. Preferable with small data transfer or multiple computers.

Shared-Memory Systems

- Memory to be shared is in the address space of a particular process, which makes system calls to make that memory public for one or more other processes.

- Other processes must then make system calls to attach the shared memory to their address space

- few messages passed back and forth between the cooperating processes to setup the shared memory

Producer-Consumer Example Using Shared Memory

This is a classic example, in which one process is producing data and another process is consuming the data. ( In this example in the order in which it is produced, although that could vary. ) The data is passed via an intermediary buffer, which may be either unbounded or bounded. With a bounded buffer the producer may have to wait until there is space available in the buffer, but with an unbounded buffer the producer will never need to wait. The consumer may need to wait in either case until there is data available. This example uses shared memory and a circular queue. Note in the code below that only the producer changes "in", and only the consumer changes "out", and that they can never be accessing the same array location at the same time.

First the following data is set up in the shared memory area:

#define BUFFER_SIZE 10typedef struct {. . .} item;item buffer[ BUFFER_SIZE ];int in = 0;int out = 0;

Then the producer process. Note that the buffer is full when "in" is one les than "out" in a circular sense.

item nextProduced;while( true ) {/* Produce an item and store it in nextProduced */nextProduced = makeNewItem( . . . );/* Wait for space to become available */while( ( ( in + 1 ) % BUFFER_SIZE ) == out ); /* Do nothing *//* And then store the item and repeat the loop. */buffer[ in ] = nextProduced;in = ( in + 1 ) % BUFFER_SIZE;}

Then the consumer process. Note that the buffer is empty when "in" is equal to "out"

item nextConsumed;while( true ) {/* Wait for an item to become available */while( in == out ); /* Do nothing *//* Get the next available item */nextConsumed = buffer[ out ];out = ( out + 1 ) % BUFFER_SIZE;/* Consume the item in nextConsumed( Do something with it ) */}

Message-Passing Systems

- at minimum must support system calls for "send message" and "receive message".

- a communication link must be established between the cooperating processes before messages can be sent.

- there are three key issues to be resolved in message passing systems

- Direct or indirect communication (naming)

- Synchronous or asynchronous communication

- Automatic or explicit buffering

Naming

Direct Communication

- the sender must now the name of the receiver to which it wishes to send a message

- there is a 1-to-1 link between every sender-receiver pair

- for symmetric communication (in and out is the same), the receiver must also know the specific name of the sender from which it wishes to receive messages from. This is not necessary for asymmetric communication.

Indirect Communication

- indirect communication uses shared mailboxes or ports.

- multiple processes can share the same mailbox or boxes

- only one process can read any given message in a mailbox. The process that creates the mailbox is the owner, and the only one allowed to read the mailbox, but this can be transferred.

- the OS must provide system calls to create and delete mailboxes, and to send and receive messages to/from mailboxes.

Synchronization

Either the sending or receiving of messages (or neither or both) may be either blocking or non-blocking

Buffering

Messages are passed via queues, which may have one of three capacity configurations:

- Zero capacity - Messages cannot be stored in the queue, so senders must block until receivers accept the messages

- Bounded capacity - There is a certain pre-determined finite capacity in the queue. Senders must block if the queue is full, until space becomes available in the queue, but may be either blocking or non-blocking otherwise.

- Unbounded capacity - The queue has a theoretical infinite capacity, so senders are never forced to block.

Communication in Client-Server Systems

Sockets

- A socket is an endpoint for communication

- Two processes communicating over a network often use a pair of connected sockets as a communication channel.

- A socket is identified by an IP address concatenated with a port number.

- Port numbers below 1024 are considered to be well-known, and are generally reserved for common Internet services. For example, telnet servers listen to port 23, ftp servers to port 21, and web servers to port 80.

- General purpose user sockets are assigned unused ports over 1024 by the operating system in response to system calls such as socket() or socketpair()

- Communication channels via sockets may be one of two major forms:

- Connection-oriented (TCP, Transmission Control Protocol) connections emulate a telephone connection. All packets sent are guaranteed to arrive in good condition, and the order in which they were sent. The TCP layer of the network protocol takes steps to verify al packets sent, re-send if necessary and arrange received packets in proper order.

- Connectionless (UDP, User Datagram Protocol) emulate individual telegrams. There is no guarantee that any particular packet will get through undamaged ( or at all ), and no guarantee that the packets will get delivered in any particular order.

Remote Procedure Calls, RPC

- The general concept of RPC is to make procedure calls similar to local procedures, except the procedure being called lies on a remote machine.

- Implementation involves stubs on either end of the connection.

- The local process calls on the stub, much as it would call upon a local procedure.

- The RPC system packages up (marshals) the parameters to the procedure call, and transmits them to the remote system.

- On the remote side the RPC daemon accepts the parameters and calls upon the appropriate remote procedure to perform the requested work

- Any results to be returned are then packaged up and sent back by the RPC system to the local system, which then unpacks them and results to the local calling procedure

Pipes

- Pipes are one of the earliest and simplest channels of communications between UNIX processes

- There re four key considerations in implementing Pipes

- Unidirectional or bidirectional communication

- Is bidirectional communication half duplex or full duplex

- Must a relationship such as parent-child exist between the processes?

- Can pipes communicate over a network, or only on the same machine?

Ordinary Pipes

ordinary pipes are uni-directional, wit a reading end and a writing end. (If bidirectional, then a second pipe is needed)

Ordinary pipes are created with the system call:

int pipe ( int fd [ ] )- the return value is 0 on success, -1 if an error continues

- the int array must be allocated before the call, and the values are filled in by the pipe system call

fd[0]is filled in with a file descriptor for the reading end of the pipefd[1]is filled in with a file descriptor for the writing end of the pipe

- ordinary pipes are only accessible in the process that created them

- typically a parent creates a pipe before forking a child

- when the child inherits open files from its parent, including the pipe file(s), a chanel of communication is established

- each process (parent and child) should first close the ends of the pipe that they are not using

ordinary pipes in Windows are very similar

- Windows terms them anonymous pipes

- they are limited to parent-child relationships

- they are read from and written to as files.

- they are created with CreatePipe() function, which takes additional arguments.

- it is necessary to specify what resources a child inherits, such as pipes

Named Pipes

- support bidirectional communication, communication between non parent-child related processes, and persistence after the process which created them exits. Multiple processes can also share a named pipe, typically one reader and multiple writers

- in UNIX, named pipes are termed fifos, and appear as ordinary files in the file system.

- ( Recognizable by a "p" as the first character of a long listing, e.g. /dev/initctl )

- Created with mkfifo( ) and manipulated with read( ), write( ), open( ), close( ), etc.

- UNIX named pipes are bidirectional, but half-duplex, so two pipes are still typically used for bidirectional communications.

- UNIX named pipes still require that all processes be running on the same machine. Otherwise sockets are used.

- Windows named pipes provide richer communications

- Full-duplex is supported

- Processes may reside on the same or different machines

- Created and manipulated using

CreateNamedPipe(),ConnectedNamedPipe(),ReadFile(), andWriteFile()